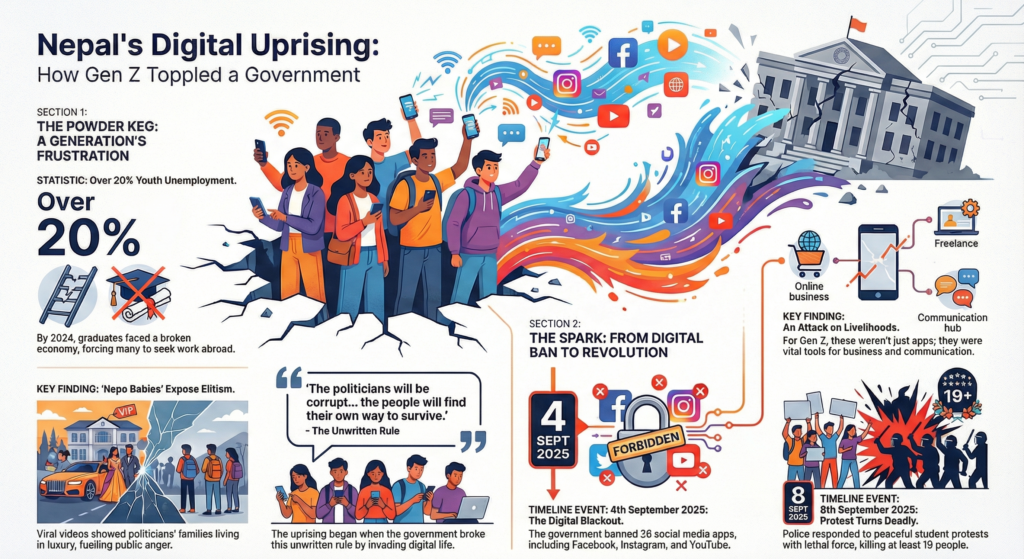

The Great IPO Purge: Why Nepal’s Regulators Are Finally Pulling the Brakes

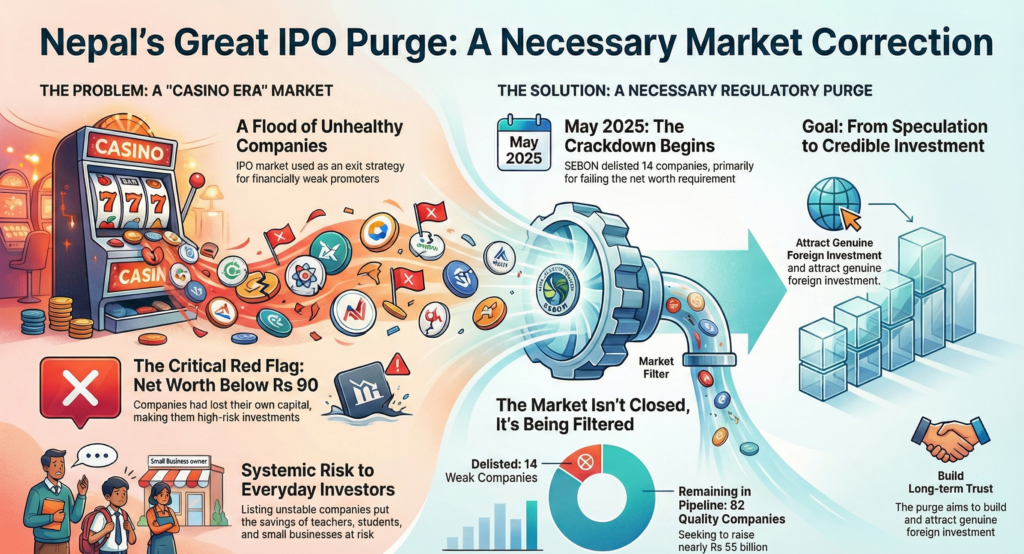

If you have been following the Nepali stock market over the last year, you might have felt a distinct shift in the air. For a long time, the Initial Public Offering (IPO) market felt like an unending party where everyone was invited, regardless of how shaky their financial shoes were. But in May 2025, the music stopped—at least for some.

The Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON) abruptly delisted 14 companies from its IPO pipeline. Among the casualties were five major players in the hotel and tourism sector, including names like Apex Hospitality and Annapurna Cable Car. This wasn’t just a paperwork error or a bureaucratic delay. It was a purge.

For years, the narrative in Kathmandu has been that we need to flood the market with companies to democratize wealth. But when regulators finally looked under the hood, they found engines that were barely running. This crackdown on real estate and tourism IPOs is arguably the most significant regulatory correction we have seen in a decade. It is messy, it is controversial, and frankly, it is long overdue.

But to understand why this matters, we have to look past the angry press releases from disgruntled business owners. This isn’t just about a few hotels getting rejected; it is a battle for the soul of Nepal’s capital market.

Background and Context

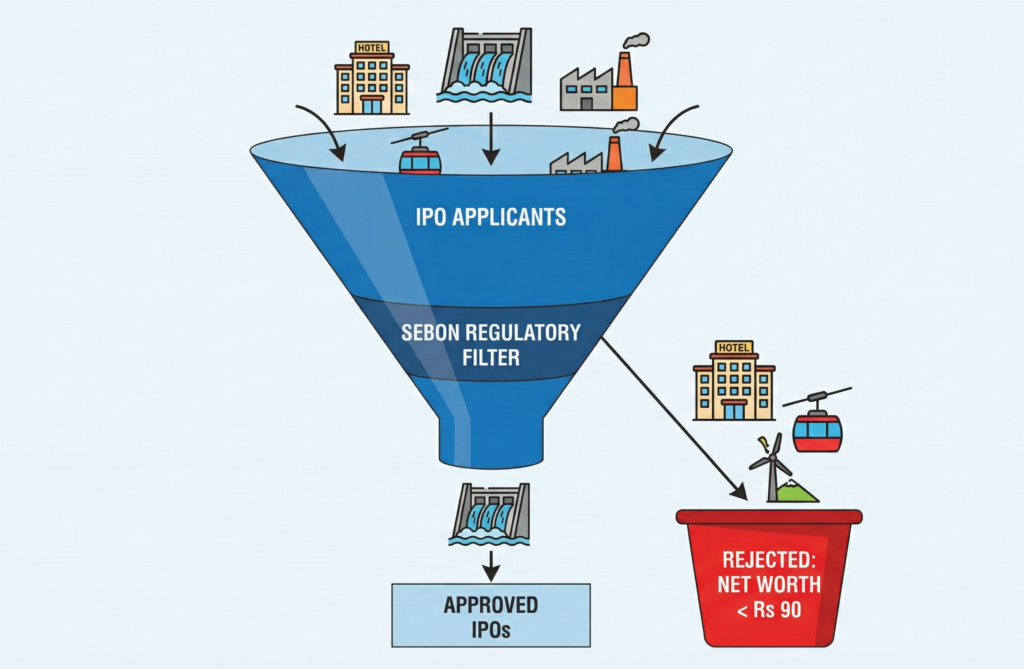

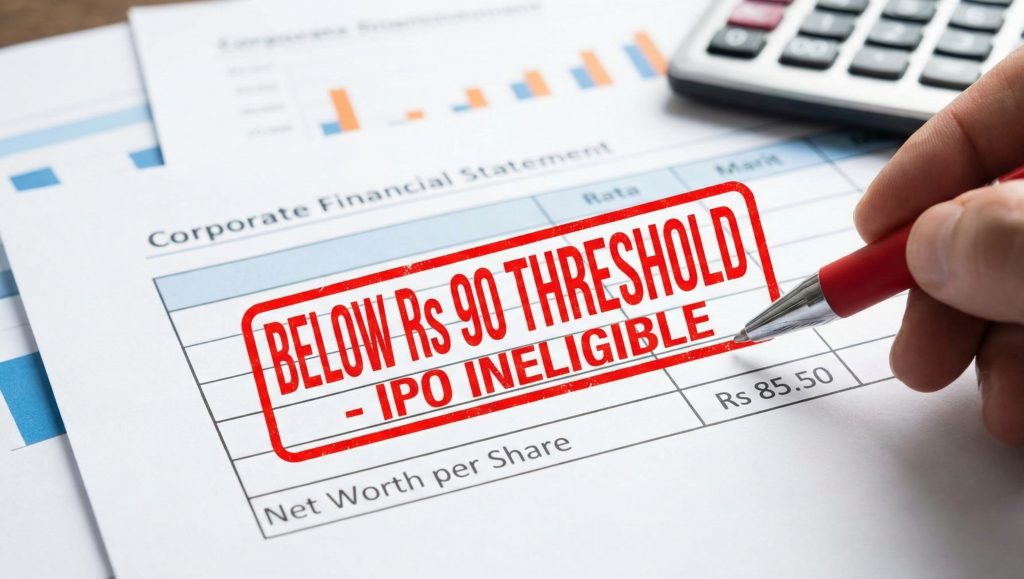

To understand the current chaos, we have to rewind to late 2023. In December of that year, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC)—a parliamentary body that keeps an eye on government spending and financial discipline—issued a directive that should have been common sense. They told SEBON to stop approving IPOs for companies with a net worth below Rs 90 per share.

Why does this number matter? In Nepal, the standard face value of a share is usually Rs 100. If a company’s net worth is below Rs 90, it effectively means the company has eroded its capital. It owes more or has lost more than it started with. When such a company asks the public for money at Rs 100 (or more) per share, they aren’t offering you an investment; they are asking you to bail them out.

For a while, this directive sat like a dormant volcano. SEBON, under its previous leadership, dragged its feet. But the pressure mounted. By May 2025, following raids by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) and a leadership vacuum left by the departure of former chairman Ramesh Kumar Hamal, the regulator finally acted.

They removed 14 companies from the pipeline. While one hydropower company was booted for having a Power Purchase Agreement valid for only five years, the vast majority—13 out of 14—were kicked out because their net worth was below that critical Rs 90 threshold. The hotel and tourism sector, which had been banking on public money to recover from the post-COVID slump, took a heavy hit.

The Real Issue

Here is where things get interesting, and where the polite business reporting usually stops. The “setback” in tourism IPOs is not a story about government red tape strangling entrepreneurship. It is a story about the end of the “casino era” in the Nepali stock market.

For too long, the IPO process in Nepal has been treated as an exit strategy for promoters rather than a growth strategy for companies. When a hotel like Thamel Plaza Hotel and Suites or Prabhu Helicopters gets removed from the pipeline, we need to ask why they were there in the first place if their financials were so fragile.

The argument from the industry is that tourism was decimated by the pandemic and needs capital to rebuild. That is a valid point. However, the stock market is not a charity. It is a place for the public to buy a piece of a profit-generating asset. If a company has a net worth below Rs 90, it is technically struggling to keep its head above water. Listing such companies poses a systemic risk to retail investors—the teachers, students, and small business owners who make up the backbone of NEPSE.

Furthermore, we cannot ignore the elephant in the room: regulatory capture. The fact that former SEBON chairman Ramesh Kumar Hamal is under investigation by the CIAA for allegedly approving financially weak companies tells you everything you need to know. The system was rigged to prioritize the issuance of shares over the quality of shares.

The “Real Estate” crisis in the IPO market is actually a crisis of valuation. Real estate and hotel developers have been used to inflating asset values to secure bank loans. When they tried to bring those same shaky valuations to the public market, the PAC finally drew a line in the sand. This isn’t a setback; it’s a safety barrier.

What Most People Miss

In the noise of the headlines, several nuances are getting lost.

First, the narrative that “Nepal is closed for business” is factually incorrect. While 14 companies were removed, as of December 2025, there are still 82 companies in the pipeline seeking to raise nearly Rs 55 billion. The market isn’t dead; it is just being filtered. In fact, six hotel and tourism companies, including Akama Hotel and Varnabas Museum Hotel, remained in the active pipeline as of August 2025 because they presumably met the financial criteria.

Second, people are conflating the IPO crackdown with the failure of the 2024 Investment Summit. It is true that the summit was a disaster—attracting zero foreign Letters of Intent (LOIs) for the 12 showcased projects. But that wasn’t because SEBON tightened IPO rules in 2025. That failed because the projects weren’t ready. When you pitch investors without clear data on land acquisition or tax terms, they walk away. Blaming the IPO regulations for the lack of foreign investment is a convenient excuse for poor project preparation.

Third, look at the Reliance Spinning Mills debacle. This company was approved for an IPO despite having unpaid electricity bills exceeding Rs 1.71 billion. SEBON’s new leadership, including Chairman Santosh Narayan Shrestha appointed in July 2025, has pledged to fix things, yet this approval slipped through based on two-year-old financial statements. This proves that while the “purge” of the 14 companies was a good start, the regulator is still prone to massive lapses in judgment. The system is correcting, but it is still deeply flawed.

What This Means for Nepal

The implications of this crackdown extend far beyond the share prices of a few hotels.

Short-Term Pain: We will see a slowdown in the “real estate” cycle. Developers who planned to use IPO funds to pay off bank loans are now stuck. This might lead to an increase in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) for banks that are heavily exposed to the hospitality sector. We are already seeing cooperatives face liquidity crises; this pressure will likely move upstream to commercial banks.

The Credibility Test: For the average Nepali, this is a test of trust. If SEBON holds the line on the Rs 90 net worth rule and implements the proposed strictures—like increasing the minimum lot size to Rs 10,000 and demanding profitable history—the market will mature. It will transition from a speculative gambling den into a mechanism for genuine capital formation.

The Political Economy: This sets up a clash between the “crony capitalists” who thrived under loose regulations and the new reformist push driven by the PAC and CIAA. The fact that the authority raided SEBON in May 2025 suggests that the days of unchecked regulatory discretionary power might be numbered.

If Nepal wants to attract genuine foreign investment—not just domestic shuffling of money—our regulators need to be ruthless. Foreign investors do not buy IPOs in markets where insolvent companies are allowed to list. By purging these weak companies, Nepal is inadvertently doing exactly what it needs to do to eventually look attractive to the outside world.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Did SEBON ban all hotel and tourism companies from issuing IPOs? No. They only removed companies that did not meet specific financial criteria, specifically those with a net worth below Rs 90 per share. As of August 2025, several tourism companies like Hotel Forest Inn and Mountain Glory Limited were still in the pipeline. The door is open, but only for financially healthy companies.

2. What does the “Rs 90 Net Worth” rule actually mean? Think of it this way: If you put Rs 100 into a business, and after a few years the business has lost money so that only Rs 85 of value remains for every Rs 100 invested, that business has a net worth of Rs 85. The government is saying: “If you have lost that much of your own capital, you are not allowed to ask the general public for more money.” It is a rule designed to protect you from buying into debt-ridden companies.

3. Is the IPO market closed right now? Not at all. While there was a long pause in approvals between late 2024 and mid-2025 due to the investigation into the former chairman, the process has restarted. There is a massive backlog of over 80 companies waiting for approval. However, under the new leadership and stricter scrutiny, the pace of approval will likely be slower, and hopefully, the quality of companies will be higher.